Byron History

It is hard for us to imagine what the Byron area looked like on the other side of yesterday. The story begins with Native Americans that lived throughout the Delta region. It continues with Spanish explorers, early rancheros and vaqueros tending their cattle, and the trappers, mountain men and wilderness wanderers that ventured west.

Hundreds of years ago, Yokut Indians roamed this region of California. They lived in crude huts of brush along the waterways and in caves near what is now Vasco Road. The Indians lived off the land, searching for food obtainable from roots, acorns and other nuts, seeds, and wild clover as well as a plentiful supply of salmon, waterfowl, antelope and deer. Treats were scrounged from the ground during root gathering. A type of flatworm was used in acorn flatbread for shortening and earthworms and grasshoppers were considered a delicacy.

As a young person, I went on many family outings to the Vasco Caves, where an endless supply of Indian artifacts could be found. It was not unusual to come home with a pocketful of arrowheads, or even an occasional grinding stone. The caves are located about a mile southwest of a ranch where my great-grandfather, John Samuel Armstrong, settled in the mid-1800’s.

Like most California Indians, the Yokuts wore little clothing; women wore skirts made of bark fiber, tule or deerskin, and the men were usually naked, though sometimes they wore a deerskin breechcloth. The Yokuts were a peaceful people, and unfortunately, ill prepared for the white man. Disease, a declining birth rate, high infant mortality and warfare cut into the tribe’s population. In 1883, a cholera epidemic further decimated the people, and by 1900, the state’s Indian population had dropped from 150,000 to less than 16,000.

The Spanish were the first white men to discover the Byron area. In 1772, a group of Spanish soldiers led by Captain Fages and Fray Crespi explored Mount Diablo and the surrounding area. Over sixty years passed before the region was deeded to Don Jose Noriega in 1835. In 1836, Doctor John Marsh purchased a ten-by-twelve mile parcel (17,000 acres) from Noriega for $500, about three cents an acre.

At that time, oaks grew so tall that wild cattle and antelope could trail beneath them in countryside abundant with wildlife. Elk, deer, antelope and bear grazed throughout the region, along with wild mustangs and spotted cattle originally introduced to the area by Mission fathers.

John Marsh’s rancho extended from Mount Diablo to the San Joaquin River. He is credited with soliciting immigration to California from the East. Wishing to see California become part of the United States, Marsh wrote glowing letters of the area’s attributes and attractions to friends back east. These letters were wildly published in newspapers and directly influential in encouraging pioneers to cross the Sierra Nevada to the San Joaquin Valley.

Today, as we see railroads, highways and planes overhead, attempting to visualize rolling hills covered with groves of oak trees and luxuriant growth of perennial grasses and wildflowers is difficult at best. But this is what the first immigrants saw in 1841, when the Bidwell-Bartleson wagon train arrived at the Marsh Rancho and began the settling of California as we know it today.

Stock raising was a principal part of life here during the 1840’s and ‘50’s. This region of California offered miles and miles of good pastureland, with natural springs and cool streams in the foothills of Mount Diablo, allowing cattle to grow fat on wild oats, clover and alfalfa. For many years, the whole territory operated under a free-range system, until wheat farmers began settling in the regions. Roaming livestock became a threat to vulnerable crops, and by the late 1960’s barbed wire had been introduced to fence rangeland.

Point of Timber played a large part in the history of Byron as an important shipping point for early settlers of the area. Located where Bay Cities Building Materials (on Highway 4) is today, Point of Timber had the area’s first post office, school, church, general store, Grange hall and stage stop. A landing for shipping wheat, jointly built by neighboring farmers and known as Point of Timber Landing, offered local wheat growers a facility to ship their products to market.

By the early 1860’s, many young families had settled in East Contra Costa to farm the rich soii found there. These families were known as “sky farmers” because they depended on nature for their crops’ development. Locally grown wheat was stored in large warehouses near Point of Timber Landing until it could be loaded on schooners or barges headed for Carquinez or Port Costa docks to be transferred onto larger vessels bound for ports all over the world.

Wheat was the chief industry of Contra Costa County in the 1860’s. Thousands of acres of the golden grain were sowed in the Byron region. The first farmers planted their seeds in the fall, leaving the seed to lie on the ground all winter while the rains softened the hard soil. With the warmth of spring, the crop of wheat sprouted, and by summer it was ready to harvest.

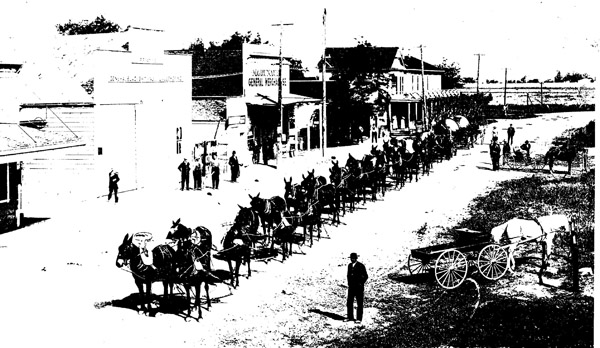

The town of Byron was actually founded in 1878 when the San Pablo and Tulare Railroad Company (later the Southern Pacific) built a track from Martinez to Banta, creating a direct line from Contra Costa County to the San Joaquin Valley and transcontinental service.

A cobbler named Smith (who mended boots and saddles) constructed Byron’s first building. The first home was built by Fred Wilkening, and in the fall of 1878, a post office was established (Wilkening became the first postmaster). The area drew a mixture of nationalities, cultures and styles, and by the end of 1878, Byron consisted of a hotel, cobbler’s shop, saloon, post office and railroad depot.

You can’t look at early Byron history without mentioning Byron Hot Springs, a luxurious resort nestled in the foothills two miles southwest of town. The springs were famous for their mineral waters from the time of the California Indians until 1938, when the resort closed. In its heyday, Byron Hot Springs drew people from all over the United States and Europe to bask in the warm sunshine and soak in the healing waters. Doctors would recommend the springs for relief of indigestion, ailments of the stomach and liver, rheumatism and gout. During World War II, the government purchased Byron Hot Springs Resort for use as an interrogation center.

When most of us think of history, we think in terms of great events and famous personalities that have played roles in building the nations of the world. Yes, it is clear to me that each of Byron’s pioneers left a footprint in our past. Byron’s history can be traced from frontier days to modern times; from open range to fenced pastures; from wagon trains to the railroad; from dry farming to irrigated fields; from makeshift and make-do to more convenient, easier ways of life.

Unfortunately many of Byron’s landmarks are falling to time each year, as fire, development and “progress” take their toll. The wonderful brick Byron Times building of my childhood has been replaced with a modern convenience store. There is nothing left of the Byron Hot Springs resort except a shell of the once luxurious hotel; many of the beautiful oak trees of the Vasco region now lie under the Los Vaqueros Reservoir, and so it goes.

***********************************************************************************************

Reprinted from “East Contra Costa County Footprints in the Sand” by Kathy Leighton in 2001.

Permission to reprint this article was granted by Kathy Leighton.

Main Street, Byron, circa 1910